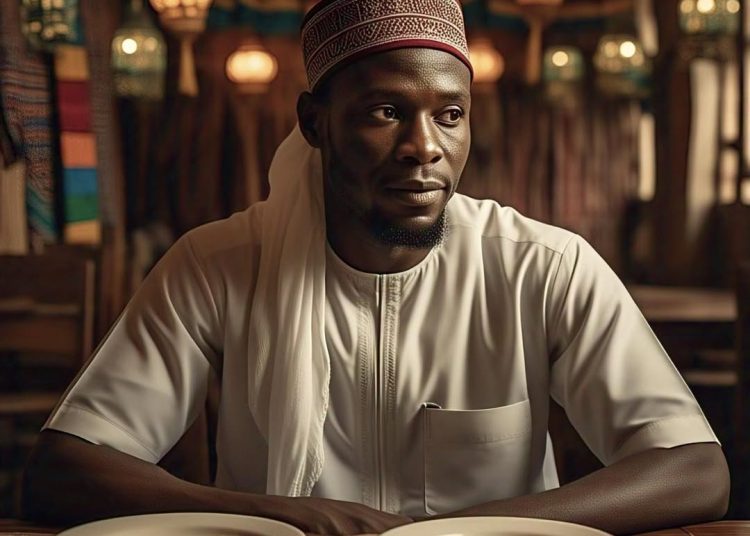

Ramadan has ended, but the hunger has not. As the crescent moon signals the close of the holy month, Malawi’s Muslim community exhales—not in celebration, but in exhaustion. What should have been spiritual renewal became a test of survival. Fasting from sunrise to sunset was the easy part. The real trial came at iftar and suhoor, when families stared at near-empty plates, their hunger stretching far beyond the sacred hours of abstinence. For them, this was not just Ramadan. It was the fasting that never ended.

A Fasting Within a Fasting

In the villages of Mangochi, just like other many districts where maize fields withered under erratic rains, the Ramadan table was stripped to its barest form. No ‘Uji’ (porridge) to break the fast, no ‘Zitumbuwa’ (African cakes)—just pumpkin, if they were lucky. The same pumpkin for suhoor, the same pumpkin for iftar. A cruel irony: a month meant to simulate hunger had become a mirror of Malawi’s unrelenting food crisis.

What made this reality more painful was the religious obligation to still provide proper meals at dawn and sunset—not just for those fasting but for family members exempted due to illness, age, or other valid reasons. The elderly grandmother too frail to fast, the child too young, the chronically ill relative—all still needed nourishment that few households could adequately provide.

“We have been receiving visitors on a daily basis asking for help with farm activities. In return, we give them pumpkins that they can use for breakfast as well as other meals,” says Edesi Dyton from Namwera, Mangochi. These strangers trek for miles, begging to work her land in exchange for a single pumpkin. They leave with hollow cheeks but full hands. What else can she give them?

In cities, the crisis wore a different face—empty wallets instead of empty fields. Salaried workers who once broke their fast with bread now stared at price tags in disbelief. A loaf? A luxury. Cooking oil? A dream. Rice—the heart of every Malawian iftar—vanished from pots, replaced by whatever could stretch furthest. Even Irish potatoes, despite rising prices, became precious commodities, offering more sustenance per kwacha than the increasingly unattainable bread.

The Silence of the Communal Table

Ramadan is supposed to echo with shared meals, laughter, and generosity. But this year, the communal tables stood barren. Islamic charities, once lifelines, buckled under the weight of inflation. Some managed only token gestures where previously they had fed thousands. Others disappeared entirely from the charitable landscape, themselves victims of the economic downturn.

“As an individual, I used to organize iftar for my extended family and friends. This time around I have failed to do so. I distributed only sugar to my very close family members, and not many at that. Even during Eid, I could previously organize a feast that would feed more than 30 people, but I can’t see that happening this year,” says Dicks Suman, a small business owner in Mangochi central. Before, they gave from their excess. Now, they give from their hunger.

And then comes the final blow: zakat al-fitr. The obligatory charity, meant to purify the fast, instead laid bare the depth of the crisis. At Lilongwe’s city center mosque, the announcement during the final Friday prayer in this year’s month of Ramadan brought this reality into sharp focus: those paying in cash must contribute 6,500 kwacha (representing 2.5kg of maize flour) or 10,000 kwacha for the equivalent amount of rice—sums that might as well have been millions for parents choosing between faith and feeding their children.

Sheikh Omar Nkachelenga from Blantyre Islamic Mission offers a grim consolation: “If a person has no food or money, that person is eligible to receive zakaat and not pay.” But in a country where everyone scrapes the bottom, who is left to give? How many are eligible to receive zakaat now in Malawi given the extent of the crisis?

Eid Without Joy

Eid al-Fitr should be a riot of color, laughter, and feasting. But this year, mothers stitch old clothes instead of buying new. They are told by their husbands, “wear old clothes. Just change the masjid”. The elaborate Eid meals of previous years exist only in memory, replaced by hopes for any meal at all.

Government’s Steady Hand

In the heart of Mangochi, Machinga, and Zomba—where Muslim brothers and sisters stand strong in faith—the government is extending a hand of compassion. The President’s donation of cows, rice, and cooking oil is being distributed in these districts, a lifeline for those who have endured hardship with unwavering resilience.

This special Eid donation comes as part of the government’s ongoing efforts throughout the economic crisis. The administration has been delivering social cash transfers, creating opportunities through NEEF, and ensuring relief reaches the most vulnerable. It is a race against time, a battle against forces beyond any one nation’s control: disasters, the scars of COVID-19, and a world gripped by economic storms.

Even with these tireless efforts, some still wait in the shadows of need. No leader can promise to save everyone, but this administration refuses to stand by while its people suffer. Every measure taken, every bag of grain delivered, is a testament to their commitment—not because it is easy, but because it is right.

While the presidential Eid donation cannot reach every household in need, it represents a meaningful acknowledgment of the community’s struggles and a concrete step toward easing the burden of celebration for many Muslim families.

Faith Amid Disasters and High Inflation

Yet, in this crucible of suffering, something profound has emerged. A faith not of feasts, but of fortitude. A Ramadan not of abundance, but of raw dependence on Allah. Muslims across Malawi speak of a deeper understanding of the month’s purpose—to experience hunger so as to better understand the hungry, to recognize one’s dependence on Allah when all material supports fall away, to find strength in community when individual resources fail.

As the call to Eid prayer rings out tomorrow in Malawi, it finds a people humbled but unbroken. The hands raised in prayer may tremble with weakness, and the festive clothes may be faded from many wearings, but the faith that sustained believers through this challenging Ramadan remains vibrant—a testament to spiritual wealth amid material poverty.

For Malawi’s Muslims, this Ramadan concludes not as the experience they would have chosen, but perhaps as the one they needed—a reminder that when the hunger of religious observance meets the hunger of economic reality, faith finds its deepest expression not in ritual perfection but in steadfast perseverance against overwhelming odds. When the body starves, the soul still feasts.

The road ahead remains steep, but Malawi will walk it together.

Are We Too Small for Political Courage?

The moment Adil Chilungo walked into that nomination hall on July 24, 2025, he wasn't just carrying his papers—he was...

Read more