Yesterday, I posted a simple preview of this article on social media. Within hours, fellow Muslims flooded my inbox with messages—not engaging with the content, but demanding to know why I wasn’t promoting “the Muslim party” or “our candidate” instead. Some questioned my faith, others my loyalty. The swift backlash revealed something profound: in Malawi, challenging UDF loyalty still feels like challenging Muslim identity itself.

This reaction isn’t surprising. For years, political allegiance among Malawian Muslims has been tied firmly to the United Democratic Front (UDF). But as the 2025 election approaches, something significant is shifting. Muslims are increasingly defecting from the once-automatic alignment with UDF—not because they reject what UDF once represented, but because they’ve witnessed how following UDF into alliances, particularly with the DPP, has systematically weakened rather than strengthened their political position.

This defection didn’t happen overnight. It’s the culmination of seeing how the DPP effectively “finished” UDF as a major political force while exploiting UDF’s connection to Muslim voters. With the UDF now diminished through these political maneuvers, Muslims are defecting from a strategy that no longer serves their interests—the strategy of automatically following UDF’s lead regardless of outcome.

The UDF Era: When Party and Identity Were One

You can’t talk about the political awakening of Malawian Muslims without mentioning Dr. Bakili Muluzi. Back in 1994, when he became the first multiparty president—and a Muslim from the Yao tribe at that—it was a game-changer. For a community that had long felt sidelined, having one of their own in charge was huge. Naturally, this led to a tight-knit bond with the UDF.

This wasn’t just about politics; it was about identity. Supporting the UDF became almost synonymous with being a “true Muslim,” especially among the Yao. It was a mix of religion, culture, and politics that made Muslims feel seen and heard. But, like any relationship built on convenience, it had its cracks.

A History of Political Betrayal and Strategic Exploitation

The complicated relationship between UDF and DPP has deep historical roots that have profoundly shaped Muslim political identity in Malawi. During the 2004 general elections, Bakili Muluzi handpicked Bingu wa Mutharika (Peter Mutharika’s late brother) to lead UDF. Though Bingu won with a landslide victory, the relationship quickly soured as he accused Muluzi of trying to “rule from the backdoor.”

In a move that shocked UDF supporters, Bingu abandoned the party that had brought him to power and formed the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2005. This betrayal created deep wounds among UDF followers, including its Muslim base, who felt their loyalty had been exploited. The UDF, which had been in government since 1994, found itself in opposition overnight. A sharp division emerged among UDF supporters—some remained loyal to the party, while others followed Bingu to the DPP but faced backlash from their communities for this perceived betrayal.

The impact on Muslim political representation was immediate and severe. Bingu’s Vice President, Cassim Chilumpha, a Muslim, was arrested on treason charges as tensions escalated between the UDF and the newly formed DPP. Later, Bakili Muluzi himself was arrested on corruption charges—moves many Muslims viewed as politically motivated attacks on their leadership.

What’s often overlooked is how the DPP began systematically altering the demographic makeup of Muslim-majority areas. During Bingu’s presidency, he introduced a program called “Kudzigulira Malo” (a population resettlement program), ostensibly aimed at moving people from highly populated areas to less populated regions. However, in practice, many people from the Lomwe belt (Bingu’s ethnic base in Thyolo and Mulanje) were relocated to already densely populated Muslim-majority areas in the Eastern Region like Mangochi and Machinga. Surprisingly few, if any, were deployed to the Lomwe belt itself. This strategic population movement established DPP voting blocs within traditional UDF strongholds, making it easier for DPP to capture seats in these areas up to the present day.

During the 2009 elections, Muluzi attempted to stand for a third term but was barred by the Malawi Electoral Commission because he had already served his constitutional two terms (1994-2004). Without a strong candidate, UDF supported the MCP, but still lost to Bingu’s DPP, who selected Joyce Banda as his running mate.

When Bingu died in office in 2012, Joyce Banda constitutionally assumed leadership as Vice President, despite having formed her own People’s Party. This created another complex dynamic for Muslim voters. Banda, a Yao from the Muslim-majority area of Zomba, had natural connections to the Muslim community. However, the 2014 elections revealed deep divisions, with staunch UDF supporters actively campaigning against her, some even misinterpreting religious scriptures to argue that a woman should not be a leader.

It wasn’t until 2014 that UDF regained some momentum, when Atupele Muluzi, Bakili’s son, was elected to be the party’s torch bearer. He ran for president on the UDF ticket with his “Ung’ono Ung’ono” youth-focused campaign that resonated with many young voters. However, he lost to DPP’s Peter Mutharika, who won the presidency, further cementing the DPP’s dominance.

By 2019, the political landscape had shifted dramatically. The UDF formed an alliance with the DPP that many Muslim supporters welcomed, hoping it would strengthen their political position. However, this alliance ultimately served the DPP’s interests at UDF’s expense. The DPP managed to plant its candidates in traditional UDF strongholds, especially in Muslim-majority areas. The outcome was a systematic weakening of the UDF’s parliamentary presence, with many long-serving MPs losing their seats to DPP newcomers.

What’s crucial to understand is that when Muslims voted for these DPP candidates, they weren’t abandoning UDF loyalty—they were following UDF’s lead into what they believed was a beneficial alliance. The community’s 90% Yao majority continued supporting candidates affiliated with this alliance out of their traditional loyalty to UDF, hoping for positive outcomes from the partnership.

The ultimate letdown came when President Peter Mutharika picked Everton Chimulirenji as his running mate instead of Atupele Muluzi, despite high hopes within the Muslim community. This choice signaled that even in partnership, Muslim political needs were an afterthought. After winning the election, Mutharika appointed Atupele to a ministerial position, which many saw as insufficient consolation.

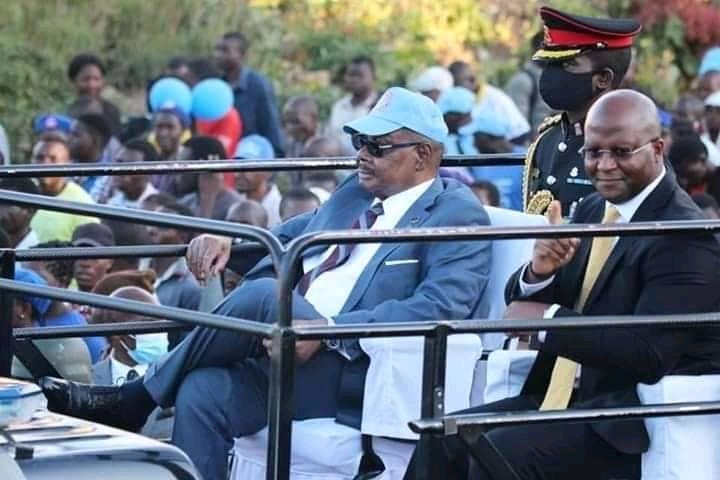

When the High Court annulled the 2019 election results due to irregularities, it led to the 2020 presidential rerun under the new 50+1 rule. For this election, Peter Mutharika did select Atupele Muluzi as his running mate on the DPP ticket, which excited many Muslims. However, even this alliance wasn’t enough to secure victory against the Tonse Alliance led by Lazarus Chakwera.

This sequence of events revealed a painful truth to many in the Muslim community: the DPP had effectively used its alliance with UDF to systematically diminish UDF’s political strength while benefiting from UDF’s connection to Muslim voters. Rather than Muslims abandoning UDF, it was more that UDF had been strategically weakened through political maneuvering, leaving its loyal supporters questioning the wisdom of automatically following UDF into alliances that hadn’t served community interests well.

The Chakwera Presidency: Muslim Inclusion Amid Challenges

When Reverend Lazarus Chakwera, a Pentecostal preacher and Malawi Congress Party leader, took over the presidency in 2020, many in the Muslim community watched with apprehension. During the 2019 elections, fear spread through Muslim communities—partly fueled by propaganda claiming he planned to declare Malawi a Christian state.

His breakthrough came during the 2020 presidential rerun when he headed the Tonse Alliance—a coalition of nine parties that attracted Muslims who felt represented through various coalition members, particularly Saulos Chilima’s UTM Party, whose non-partisan message resonated with younger Muslims.

Once in office, President Chakwera confounded skeptics with what has become a presidency of Muslim inclusion. He has appointed Muslims to key government positions, including cabinet ministers, diplomatic posts, and parastatal boards, even appointing a Presidential Advisor on Islamic Affairs. The president has actively participated in Muslim events such as Eid celebrations, even donning traditional Muslim attire.

A defining moment in Chakwera’s relationship with Malawian Muslims came in late 2024 during the Israel-Palestine conflict. Malawi initially voted against a proposed ceasefire in Gaza, sparking fury among Muslim leaders. Facing mounting pressure, Chakwera’s government reversed position in the next UN vote, winning back significant goodwill.

Despite these positive steps, Chakwera’s administration has faced significant economic challenges that affect all Malawians. Hyperinflation, devaluation of the Kwacha, and skyrocketing prices have created hardship for many families. While the government has implemented mitigation measures like social cash transfers and small business loans, these have been insufficient to fully address the economic challenges.

Compounding these issues are divisions within the Muslim community itself. As Abdulrahman Shaibu Ajasi of Islamic Commission for Justice and Freedom noted: “Muslims have always struggled to support each other in leadership. There’s a tendency where they don’t want to see others succeed—they want to be the only stars in the room.”

The 2025 Election: Muslims Responding to a Transformed Landscape

As the 2025 elections approach, Malawian Muslims face a political landscape fundamentally transformed by the DPP’s systematic dismantling of the UDF. With their traditional political vehicle significantly weakened, Muslims are reassessing how to maximize their influence.

President Chakwera will be seeking his final term. Having tested his leadership firsthand, Muslims must evaluate whether his inclusive governance merits support despite economic challenges. Atupele Muluzi is mounting another presidential bid, focusing on economic revitalization plans. His campaign represents both continuity with UDF traditions and an attempt to rebuild what was lost through the DPP alliance.

The DPP faces a significant challenge with Muslim voters. Having systematically undermined UDF while exploiting its connection to Muslim voters, the party must now contend with growing awareness of this strategy among the community.

For the first time, Muslim voters are approaching an election with their loyalties dispersed across multiple parties—not because they’ve abandoned UDF values, but because the UDF itself has been so diminished that a single-party strategy no longer serves community interests.

The New Voter: Muslims Breaking the Mold

A significant defection is happening among Malawian Muslim voters. Especially among younger, educated Muslims, there’s a growing realization that continued loyalty to a UDF that has been systematically weakened offers diminishing returns.

“The time to cling to one party is no longer viable. We can’t continue putting all eggs in one basket. We must spread. This is why you see today many young Muslims standing on different party tickets,” says Ali Blessings Idi, an independent candidate aspiring to become a member of parliament.

This defection is a response to political reality: Muslims loyally followed UDF into its alliance with the DPP, hoping for positive outcomes, only to see UDF’s parliamentary presence systematically dismantled while gaining little in return. By spreading Muslim representation across multiple parties, the community may be able to demand more significant stakes and roles than they could by remaining exclusively tied to a diminished UDF.

Still, this defection isn’t without its challenges. Traditional religious leaders and older community members often see this political flexibility as a betrayal of both Muluzi’s legacy and Muslim unity. The idea that “you’re not a true Muslim if you don’t support the UDF” still holds sway in many circles.

Strategic Voting: A Response to UDF’s Weakening

Looking at religious and ethnic minorities worldwide offers valuable lessons for Malawian Muslims. In many democracies, minority communities wield the most influence not by clinging to one party that has been deliberately undermined, but by becoming “swing voters” whose support has to be earned through meaningful engagement with their concerns.

This approach requires savvy political organization—setting clear policy priorities, communicating them to all parties, and holding politicians accountable regardless of their religious or ethnic background. It means backing candidates based on their platforms and commitment to community interests, while recognizing that the traditional vehicle for those interests (UDF) has been severely weakened.

With more Muslim candidates entering the fray across different parties, the community can ensure representation at multiple tables. This isn’t about abandoning UDF values, but about adapting to a political landscape where UDF has been “finished” as a major force, requiring Muslims to spread their influence to maintain political relevance.

Toward a Mature Political Identity

The Great Muslim Defection marks a political coming-of-age. It recognizes the hard reality that the UDF—after being systematically weakened by the DPP—can no longer effectively champion Muslim interests on its own. This defection isn’t from UDF’s historical importance or values, but from the political strategy of automatic loyalty that no longer serves the community well.

Had the Muslim community defected sooner from this strategy of blind loyalty, the DPP’s exploitation of UDF while benefiting from Muslim votes might not have been as effective. Had Muslim voters demanded greater assurances before following UDF into its alliance with DPP, their priorities might have received more attention.

As the 2025 election approaches, Malawian Muslims have an opportunity to redefine their political involvement. This defection from automatic UDF alignment allows Muslims to spread their influence across the political spectrum, creating leverage that wasn’t possible when concentrated behind a single diminished party.

The 50+1 electoral rule makes every voting bloc potentially decisive in a close contest. This reality creates an opportunity for strategic influence beyond what was possible through continued loyalty to a UDF that has been “finished” by the DPP’s maneuvers.

This defection doesn’t mean forgetting Bakili Muluzi’s historic role or denying the cultural significance of the UDF in Muslim political history. Instead, it means building on that legacy by developing a more sophisticated approach that maximizes community influence in a political landscape where UDF has been systematically undermined.

The question for Muslim voters is straightforward: Why continue automatic loyalty to a political strategy that has seen the UDF weakened and Muslim interests sidelined? The Great Muslim Defection represents a pragmatic response to this question—not abandoning UDF’s values, but abandoning a political approach that no longer delivers results.

Allah judges us by how we care for one another and seek justice, not by which party card we carry. Our political choices should reflect that wisdom.